Dates and time – from sundials to water clocks

Long ago, dates and time were calculated according to the position of the celestial bodies. From the time of the Ancient Greeks, people used sundials which told the time based on the position of the sun in the sky. But of course sundials had their limitations as they didn’t tell the time after dark or during the days when there was no sunshine.

Religious ceremonies and bureaucratic meetings took place at all times of day and evening, and as the ancient civilisations developed they began to search for a more consistent way of telling the time. That’s when water clocks – or klepsydras – were invented.

One of the oldest klepsydras was found in the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep I, who was buried around 1500 BCE.

How they worked

Early klepsydras were small floating vessels with a small hole in the bottom. The vessel was placed in a bowl of water where it gradually took on water until it sank, marking an interval of time. The water clock was used to time speeches and make sure that trials and speeches in the Athens law courts did not go on for too long.

An alternative design was a vessel filled with water that seeped out through a hole. The inside was marked with graduated lines, and as the water seeped away, the passing of time was measured by the level of the remaining water.

Later the Romans invented a klepsydra which measured the time of day and night. Water from a reservoir dripped into a cylindrical vessel whose sides were marked with a scale showing the hours. The level of the water was shown by a float which provided the readings against the scale on the cylinder.

Bells and whistles

Gradually the design and accuracy of water clocks was developed. The flow of water was made more constant by regulating the pressure, and clocks were mechanised.

Clocks were designed for fun, with ringing bells and gongs, or opening doors and windows showing figures of people or astrological models of the universe. Describing a water clock of his time, the Roman architect and author Vitruvius wrote, ‘statues move, goalposts are turned over, stones or eggs are thrown, trumpets blare out, and all the other amusements’.

The Tower of the Winds

In the first century BCE, a Greek astronomer called Andronikos built the magnificent Tower of the Winds in in Athens. This octagonal tower was made of marble and decorated with eight carved figures of the wind gods, and stood 42’ high in the market place where all the people could see it. It included a water clock, two sundials and a wind vane and showed not only the time but the seasons of the year and astrological dates and periods too. The klepsydra was powered by water from a spring on the Acropolis and told the time day and night.

Today

Visitors to the Roman Agora in Athens today can still see the fascinating Tower of the Winds (pictured above). Closer inspection of the marble frieze on the tower’s eight sides shows that each god represents the wind blowing from the direction he faces. Older visitors may be pleased to note the Ancient Greeks’ respect for age: whilst the gods of gentle gusts are represented by young men, the gods of strong winds are all old bearded men.

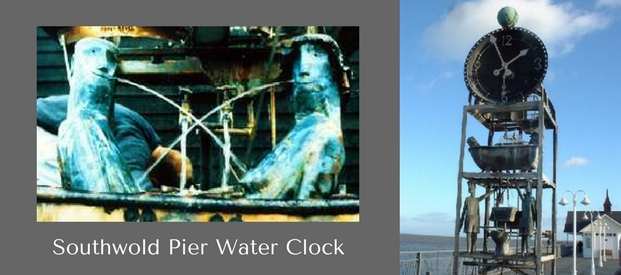

Various other modern water clocks can be found around the country. One such water clock is located on Southwold Pier in Suffolk. A bathtub balances atop a four storey platform, with a clock face at the top and statues seated in the tub. The piece was built in 1998 by Tim Hunkin and Will Jackson, originally to demonstrate water recycling, and has been on the pier since 2001. Open to the elements of the sea and wind, the clock is no longer water powered, but provides a fun spectacle to watch – with water coming out of many orifices, ending with tulips growing.

The remains of another water clock worth a mention are located in London’s Covent Garden in Neal’s Yard. Created in 1982 also by Tim Hunkin and Andy Plant, it originally adorned the front of Michael Loftus’s Neal’s Yard Wholefood Warehouse. Commissioned as an attraction to draw people to the shop it was designed and made in six weeks. On the hour water would cascade down the side of the building, causing a carefully arranged sequence of bells to chime as it descended towards the clock face. Meanwhile, six green characters would tip their watering cans to fill a tank behind the shop signage. As the water level rose, floating plastic flowers rose into view as if they had suddenly ‘grown’. The figure on the far left could swivel out to the street and spray water on to pedestrians below. The clock hasn’t worked for some time, but still remains for visitors to admire.